Supplied by Linda Newstrom-Lloyd and Angus McPherson, Trees for Bees NZ

Willows (Salix) are eminently useful on farms because they have multiple uses, propagate easily by poles or cuttings, and provide significant pollen for bees. Bee colonies coming out of winter rest can build up brood extremely fast when they are working willows, so beekeepers prioritise apiary sites near willows. Very few other plants can out-perform willows in delivering plentiful high-quality pollen and providing rapid pollen foraging efficiency for bees.

When bees are on willow pollen, the population build-up of bee colonies can be so fast that beekeepers must watch out for bee swarming and make colony splits accordingly. Such speedy and reliable bee population build-up is critical to get bee colonies to the right colony size for optimum pollination services and honey harvesting. Crude protein content in the pollen is high – from 20 % to well over 25% (unpublished data Trees for Bees NZ).

Few other bee forage plants are flowering so early in spring. One alternative to willow is five finger (Pseudowintera arboreus), but it does not grow readily in all types of climates and soil conditions; and is prone to browse damage by possums and deer.

Other alternative species such as gorse (Ulex europaeus) and broom (Cytisus scoparius) are invasive and both species are restricted by regional council plant pest control programs. They are not desirable plants for most farmers or conservationists and are not recommended for planting for bees.

Tree lucerne or tagasaste (Chamaecytisus palmensis) finishes flowering too early in the spring, although it does play an important role from late winter to very early spring.

Although these alternatives to willow are excellent bee forage, willows are the most practical to plant and maintain so beekeepers often rely on willows as the best option for spring build-up.

Advantages of Willows

Willows play an important role in agriculture and environmental management. The New Zealand Poplar Willow Research Trust (NZPWRT) has been breeding and providing high-quality willow species and genotypes (genetically identical cuttings or poles) for many years for farmers and landowners (contact Trevor Jones or Ian McIvor at www.poplarandwillow.org.nz.)

Willow trees and shrubs are used on farms and public land for land stabilisation, riparian protection, paddock shade and shelter, and shelterbelts. Certain willow species are excellent for basket making, especially Salix purpurea, S. viminalis and S. triandra. These basket willows are called “osiers” because their long thin branches bend easily (see www.willowworks.co.nz). Willows are also used as fodder for livestock, particularly during drought periods. For more information on which species or genotype to use see the NZPWRT website.

Getting the Right Tree

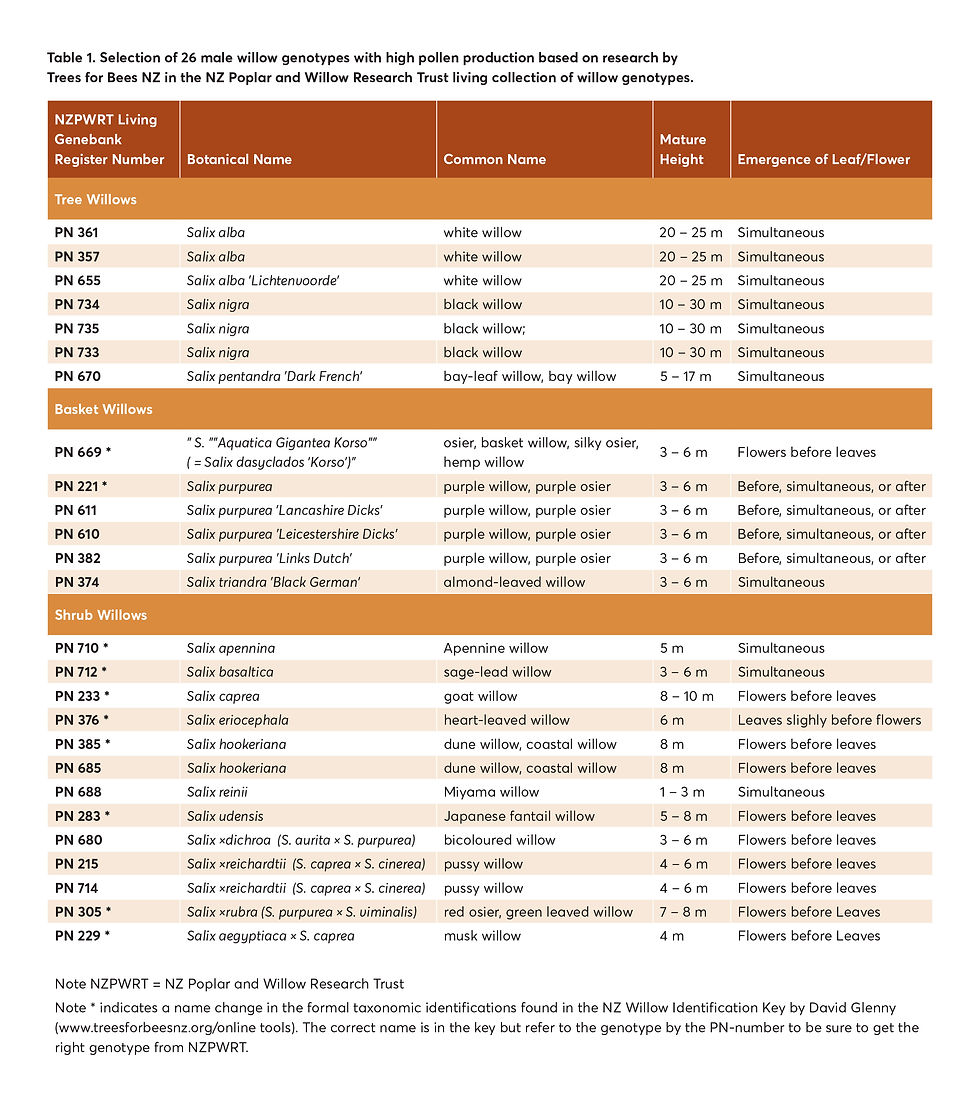

We studied the willow species and genotypes growing in the living willow collection of the NZPWRT in Palmerston North in 2014 and 2015. From our research there, we have listed the best selections of male genotypes based on the highest levels of pollen production (see Table 1).

When David Glenny of Landcare Research (Maanaki Whenua) completed his research that produced an interactive online key to identify willows, he incorporated all willow species and hybrids in the NZPWRT collection (see www.treesforbeesnz.org/onlinetools). A few names were modified during this research as reflected in the online key, but to avoid confusion when ordering poles and cuttings from NZPWRT, it is important to use the living collection register PN number as listed in Table 1.

The flowering times of the genotypes in Table 1 are shown in Figure 1. The chart demonstrates that it is possible to extend the willow flowering season to earlier months (e.g., S. aegyptiaca x caprea flowers in July) and later months (e.g., S. pentandra flowers in December). This diversity of willows will extend the willow foraging season to six months from July to December; however, most of the diversity of willow species flower from September through October (Figure 1).

Plant Males

Bees can collect pollen from male willows swiftly because male catkins provide excellent landing platforms for bees to scramble from one tiny floret to the next. The pollen is sticky, so bees quickly pack huge pollen loads in their bee baskets on their hind legs (called corbiculae) (Figure 2). Dry pollen that is not sticky is harder for bees to collect and pack into pollen pellets.

Willows trees are unisexual with male and female flowers on different trees. The male trees have only male flowers delivering both pollen and nectar while the female trees have only female flowers that deliver nectar but no pollen. The preference is to plant male trees only because they nourish bees with both pollen and nectar and reduce the risk of female willows spreading seeds.

The best willows to plant for bees are those willow species with larger catkins (e.g. S. caprea, S. hookeriana) or longer catkins (e.g. S. nigra, S. alba) since they allow faster pollen collection. Willows with very high density of catkins on the branches (e.g., S. alba, PN655) allow bees to collect great quantities of pollen from only one plant.

The tallest willow trees also deliver great quantities of pollen per square meter of footprint such as the black willow (S. nigra) and the white willow (S. alba) but the smaller multi-stemmed shrubs with densely packed large catkins can also deliver vast quantities of pollen per square meter (S. caprea, S. hookeriana).

Next month the Working with Willows series continues with a look at how to best manage the invasive nature of some willow species.

Comments